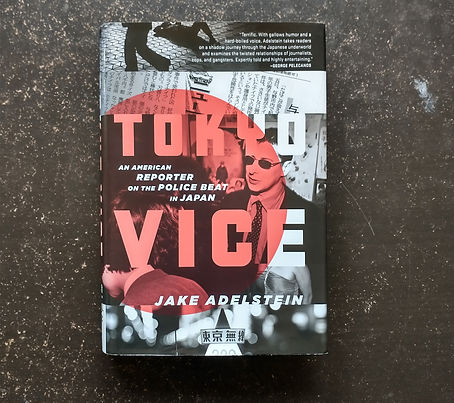

Tokyo Vice-

Jake Adelstein

The first book that caught my attention about the mafia was The Iceman, by Philip Carlo. This was around 2014. In The Iceman, Philip went into great detail about the infrastructure of the mafia and the layers and hierarchy that I had previously been ignorant of.

While the book itself has widely been debunked as a gross exaggeration fairy tale of a very loose associate of the mafia who whacked out a few flunkies in his crew by strange means, it served as a conduit to a newfound hobby: mafioso research.

I had seen all of the mainstream films like the rest of the general public but that was the extent of my knowledge. After The Iceman, I bought every mob book I could find. Murder Machine, Gas Pipe, Deal With the Devil, Underboss, Mob Boss, and Joe Dogs among many others.

In the fall I made yearly pilgrimages to New York City and bypassed going to see the Statue of Liberty and The Empire State Building in favor of taking Flatbush to Carnarsie to see the former location of the Gemini Lounge (now a church). And it became a temporary tradition to have cocktails at Sparks Steakhouse and then drunkenly lay down where Castellano was whacked by Gotti cohorts outside before leaving to see Cypress Hill.

In Chicago, when I would go out in September for Riot Fest, I would stay with friends who lived a five-minute drive away from the house where Sam Giancana was killed in Forest Park. I'd snap pictures there and then trek south towards the city proper to visit Tony Accardo's mansion.

When roughly 80% of Americans live 9 to 5 lifestyles, abide by the law, pay their taxes, and rarely deviate from the normal, the pecking order of organized swindling—where life is lived by the pistol instead of the time clock—can make for very interesting subject matter. And it's easy to become fascinated at those who spit upon the well-fortified parameters that work as mortar to keep our country intact and get away with it—very lavishly to boot.

I mostly stuck to reading into the Italian version of La Cosa Nostra and sometimes drifted off into books like The Westies (Irish mafia) and restricted my reading of cartels, low-level gangbangers, and the triad to articles. But above all, La Cosa Nostra was my steeze.

*As ludicrous as it may sound, there was something rather detestable about the other international factions of organized crime that forsook the restriction of civilian targets which kept my interest level to a low sizzle.*

When it came to The Yakuza though, that was a little different. I found them to be almost like an upper-level and intricate—almost corporate—version of organized crime. The East, in some aspects, is just so much more advanced in their respect of diligence that it spills over to almost every facet of culture, and this includes OC.

This was a preconceived notion that came to ring true in Jake Adelstein's Tokyo Vice, where his submarine venture into the underbelly of Japanese crime leaves no avenue unexplored. The intricacies of compromised authority figures, juice loans, murder, human trafficking, media manipulation, turf wars, customs, and the obscene amount of power the Yakuza possess is all brought to light through the incredibly brazen account of a journalist with an abnormal-sized set of testicles (or deficiency of brain cells) that dares to penetrate the shadow world of Japan.

For reasons that I still cannot understand, Jake Adelstein arrives in Japan in the early 90s and has his heart set on becoming a reporter.

*Even after having read the book in its entirety, I still am not clear what could be the allure of wanting to be a reporter. Especially in Japan. The process of application into one of the major newspapers is extremely complex and arduous, the entry-level dues seem completely outrageous, the demand of time is nuts, and the pay is junk. I suppose that—bereft of ever authentically knowing what the feeling of getting a scoop is like—this will be a passion that forever escapes me as a writer.*

In the bully-worship culture of Japan, Jake-san pays heavy dues for a few years and learns the ropes. Along the way he absorbs the commandments of good reporting, becomes acclimated to Japanese culture, and begins to develop sources within both the Police Force and The Yakuza.

*For a long time, I largely detested reporters as scum of the earth individuals. Movies like Absence of Malice and images of paparazzi hanging from trees and turning people's homes into prison cells (not to mention the blatant bias that has poisoned present-day reporting) have always stuck in my craw something fierce—to the point that I don't watch the news anymore. There are exceptions though like Carl Monday that shed light on scuzbuckets like George Forbes. People who use their position of power to ignore paying utility bills and get away with it. And I don't mind Geraldo Rivera and found his work in exposing the inhumane conditions at Willowbrook to be rather commendable. And then there are people like Jimmy Breslin, who, I feel as if, rather relished being in the spotlight for attention-grabbing headlines and expose's rather than providing much of a service to the general public's thirst for information. An person of whom I don't feel the least bit sorry for getting his as kicked by Jimmy Burke.*

Adelstein seems to tow the line fairly well in Tokyo Vice though and provides a narrative on what the culture in Japan is like and how to cover its ugly side without losing your life.

The subtleties may be different and nonsensical, but the landscape of sin is much the same in the East as it is in the West. And the brokers aren't much different either. Men want sex—tons of it. In Japan, the regimented approach to work also applies to leisure time, and going out to blow off steam on a Friday night offers much more at satiating man's carnal appetite than the laughable offerings do here in America.

In the States, where you pay women to put on the front of intrigue while teasing you with their assets, you are left to go home and finish off the job yourself, only with a lighter wallet (at least, that's as far as the law will allow). In Japan, (dependent upon the stamina of your libido) you can shower hop to different massage parlors for a few drinks, massage, shower, and oral happy ending to your hearts content.

All legally too.

*Strangely, you can't watch it. Hence the blurred obstruction in Japanese adult films.*

In the second half of the book, this is where Jake primarily begins to focus his investigative reporting.

In the prefecture of Roppongi, a bottom-of-the-barrel metropolis where the dregs of perversion go to play, he begins to notice the universal mask of torpor worn by women forced to perform at low rent hostess clubs specializing in female gaijin's (foreigners).

As a reporter, it is imperative to listen to your intuition and curiosity when it becomes piqued. When he does so and begins to explore the process of importing foreign women into Japan under false pretenses, it is enough to make one nauseous.

A film I saw at the beginning of 2023, Holy Spider, in which serial killer Saeed Hanaei slakes his bloodlust by picking up hookers in Mashhad, Iran and killing 16 of them, then is adorned with a hero's cloak by the public and handled with kid gloves by the government for his atrocities and the University episode of The Sopranos come close to being as monumentally jarring as the exposure of the flesh trade (and the despicable societal disregard for women in Eastern culture) is in Tokyo Vice.

*And, where I feel as if we, in the West, are far more advanced and superior in the never-ending race for human decency.*

The process—of course, paraphrased from memory—works like this: An ad is placed in various trade magazines through European countries, Australia, and even as far as Canada, offering lucrative dollars to come to Japan and work as hostesses. Inflated numbers of 100,000 yen ($10,000) per month act as the lure to bring blonde-haired and blue-eyed commodities over to Roppongi and work as (what the women who are dumped by these ads are led to believe) nothing more than strippers. They then are jammed together in small housing units where they are told that rent is 75% of their pay. Then they are forced to work as prostitutes at the club for only a fraction of what they were promised until their temporary visa expires and they become trapped under the weight of conjunctional threats from both The Police and The Yakuza.

The girls can't run to the cops because they don't care enough to prosecute the marionettes running the show and would be more likely to arrest the women for their admission of prostitution (not to mention—released back into the hands of the Yakuza to be tortured and beaten for punishment). And Yakuza goons running the show squeeze them into subservience with extortion by automatic-loans to pay back exorbitant fees that appear out of nowhere, unknowingly using their family, friends, and neighbors back home as collateral for non-payment.

It is the inhuman monsters who orchestrate these factories of hell and the complicit police force who provide them with safeguards that force Jake-san into developing a consciousness and begin using his investigative skills to liberate these poor women from a life that was no fault of their own.

Which is easier said than done.

As mentioned before, the police don't care about women who are whores (especially gaijin whores). The newspapers won't cover the story because they're owned by the Yakuza and Japanese culture regards women so far beneath men that any woman who sells her body for sex—and the inherent hell that she is enduring—is simply the karmic scales balancing out the payment for treating her vessel with such utter carelessness.

Is there victory in the end?

Small modicums I suppose.

It all depends on how one looks at it all. If I were to translate it into a language of percentages, where the prime objective of collapsing the human trafficking network in its entirety sits at 100% and no damage whatsoever at 0%, I would have to guess that it is around 28%.

Jake-san may estimate this figure to be higher or lower, but I have no clue.

It's better than nothing, that's for damn sure.

Combating the heartless specimens who perpetrate these schemes can be like punching your way out of a paper bag at times. Ariel Castro kept three girls hidden in plain sight for over a decade. And pimping—in modern day culture—is synonymous with success.

This sickening plague of human commodities is not exclusive to Japan or the Middle East. Anyone with a plain set of eyes and at least a drop of gumption in their blood can venture no further than the hotels that surround the Crocker Road Exit in Westlake or the Great Northern Blvd exit in North Olmsted to know that they are operating as low-level brothels.

The disillusionment Jake-san records experiencing, and the utter contempt these women hold for their clientele hit home with me particularly hard. I saw the same form of inner erosion begin to take foot within me after a few years in the casino industry. Much like how Jake grew to become indifferent to dead bodies outlined in chalk, or young boys stabbed to death by Yakuza for delinquent payments of their parents, or how the women seemed to hate all of the men who frequented their clubs absent of discrimination. I too began to watch as people devolved into animals and experience the throes that accompany loss with no emotion. Numb. And regarded every single one of them as nothing more than a small populace of morons. And that was across the board. Men, Women, White, Black, Asian, Indian, Middle Eastern.

Didn't matter.

I hated them all.

Sad but true.

This is a tough book to read if you are unaccustomed to bleak subject matter, because, while it can be humorous at times, it is very dark.

And not in a good way.

But such is the truth sometimes in areas we'd like to pretend do not exist. And without books like this, the victims may never have a voice.

Grade: A

Verdict: Read